USS IOWA INVESTIGATION

—NSWCDD PARTICIPATION—

By Guest Writers Paul Lefeave and Tom Doran

This article provides a short history of the incident, NSWC Dahlgren Division’s (NSWCDD) role, and some of the experiences encountered while working on the USS Iowa (BB-61) investigation. All images are U.S. Navy released unless otherwise noted.

Broadside Firing (left) and 16” Gun Firings (top) from Iowa-class Battleship

In the mid-1980s, times were great for the USS Iowa-class battleships. In addition to USS Iowa, USS New Jersey (BB-62), USS Missouri (BB-63), and USS Wisconsin (BB-64) were being recommissioned for the third time since the initial commissioning of the USS Iowa-class battleships into the Navy on 24 February 1943. This final recommissioning included an extensive modernization of all four ships, which took place from 1984–1988. During the operational years of the USS Iowa class, one thing remained constant: their mighty guns. Each ship carried three main gun turrets, each consisting of three 16"/50 caliber guns that were powerful and accurate. The guns could fire 1900-lb., high-capacity explosive or 2700-lb. armor-piercing projectiles over 22 nautical miles using 660 lbs. of propellant.

As part of the return of the Iowa-class ships, Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA) tasked NSWCDD with developing and fielding new projectiles for firing from the massive guns. By mid-1988, as part of the Naval Gunnery Improvement program, NSWCDD had developed a full caliber 16" dual-purpose improved conventional munition (DPICM) projectile (sub-munition-carrying projectile) that was in the final stages of developmental testing, in addition to the early development of an extended range sub-caliber DPICM projectile that would extend the range to over 30nm.

Wednesday morning, 19 April 1989, began like any other normal work day at NSWCDD. There would be no more “normal work” days for much of Dahlgren for many months. On that morning, there was a major malfunction of the 16"/50 caliber gun system on the USS Iowa. While conducting gunnery exercises near Puerto Rico, there was an “explosion” in the center gun of Turret 2. A call came from the NAVSEA’s 16-Inch Gun System Program Manager to Mr. Sam Burnley, NSWCDD Project Manager for the 16-Inch Gun Weapon System Improvement Program, stating that there had been an incident aboard USS Iowa involving the 16" gun. NSWCDD was told to prepare to assist NAVSEA in this investigation. News dribbled in over the next hours of the loss of the 47 sailors.

Incident Aboard USS Iowa

The tragic loss of these sailors and the effects on their families had a profound effect on those working in G Dept. as many in that department were heavily involved with the 16-Inch Gunnery Improvement Program and had worked on board USS Iowa. This day would not be forgotten. Of additional concern, the other three USS Iowa-class battleships were now sailing with their main battery of 16" guns out of service until a probable cause was identified.

When there is a major weapon system malfunction, it is standard practice to assemble a team to investigate the malfunction, determine the cause of the malfunction, and recommend corrective action(s). NAVSEA requested NSWCDD support, and G Dept. selected Mr. Burnley (G32) to lead the Dahlgren effort as part of the Navy Technical Investigation Team. Mr. Tom Doran (G32) would serve as his deputy. NSWCDD management assured there would be complete and full support of everyone at Dahlgren. No one at NSWCDD realized the magnitude of the support that would be required over the next two years. Mr. Burnley and Mr. Doran attended the initial Technical Investigation Team meeting the very next morning at NAVSEA. CAPT Joseph Miceli was appointed to lead the team. Included in this meeting were technical experts from the Navy labs whose expertise, in conjunction with Dahlgren’s unique ability to conduct full scale tests on the 16" gun system, would prove critically invaluable.

Left to right: Tom Doran, Sam Burnley, and Ray Bowen

At this meeting, the team began creating the fault tree. The fault tree process is used to: 1) identify all possible causes; 2) collect evidence to support or dismiss each cause; and 3) determine the probability of each possible cause that cannot be eliminated by direct evidence. When the Technical Investigation Team moved to Norfolk where USS Iowa was docked, a support team was also set up at Dahlgren to render support. Mr. Paul Lefeave (G61) was assigned Lead Test Engineer to plan and conduct testing at Dahlgren.

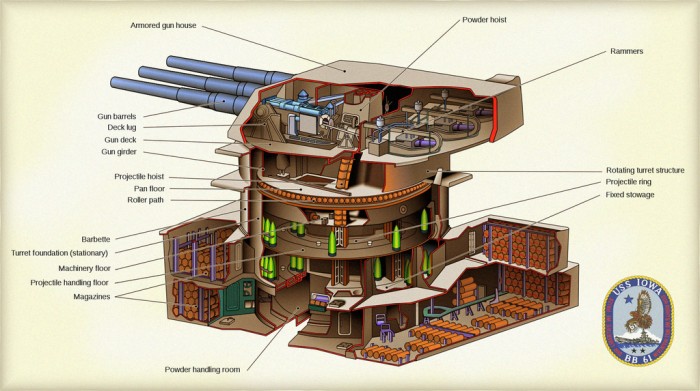

Cutaway of 16" Turret on Iowa-class Ships

Once the Technical Team was aboard USS Iowa, the job of evidence collecting began. When the team first entered Turret 2, the scene was horrific. This once beautiful machine was now a tangled mass of bent and ruptured bulkheads, downed piping and wires, and severe fire and water damage. The Navy decided to begin repairs to the turret as quickly as possible. For the Technical Team, this represented a problem in that personnel were still heavily involved in gathering evidence of the cause and effects of the “explosion.” Mr. Doran suggested to CAPT Miceli capturing a photographic record of the turret’s condition before repairs began. Miceli said “Do it.” As an example of Dahlgren’s rapid response capability, Mr. Doran called G Dept. and requested the Photo Lab send someone down immediately with a camera and a lot of film. The next day, a Dahlgren photographer and Mr. Doran spent 14 hours taking over 1000 pictures of every surface, switch, instrument, machine, and any other device in the turret that could possibly be involved. The photographer returned to Dahlgren the following day and began making color prints. These pictures were delivered to Norfolk, whereupon seeing them, CAPT Miceli ordered five more sets of prints. This took a few days and used up most of the color print paper on the east coast. This was one of Dahlgren’s first “can do” moments, but there were many more to come.

For the Technical Team in Norfolk, each workday began with an 0700 “all-hands meeting” where each member reported their plan for the day. These meetings usually lasted about 1–2 hours, after which each member left to complete their assignment for the day. At the conclusion of their long workday, the team reconvened at 1900 for several more hours. The team discussed the day’s testing, any evidence that could support their fault tree, and additional testing requirements. Often Mr. Doran or Mr. Burnley would then contact Mr. Lefeave to provide the test scenarios that needed to be conducted by the Dahlgren test team the following day. Mr. Lefeave would prepare the required test plans and urgent standard operating procedures, and call whoever was needed for the test, as well as prepare the brief for the Test Range Safety Review Board the next morning. After approvals were obtained, Mr. Lefeave and the test team conducted the test, prepared a quick-look test report, and sent the results back to the team in Norfolk. Typical work days were now 14–20 hours and, many times, seven days a week.

Testing at NSWCDD for the investigation was complex and extensive, and was conducted at a fast and furious pace while being mindful of integrity and safety. It is estimated that over 4000 test events were successfully performed over the two-year period. The dedicated Dahlgren personnel supported the USS Iowa Investigation without question or complaint, cognizant of the importance of understanding the incident to protect our military. At one point, CAPT Miceli promised everyone a long weekend for Memorial Day (six weeks after the incident), and the entire team looked forward to this much deserved break. However, on Friday afternoon before Memorial Day, a critical test scenario was identified, and everyone was called in to work that weekend. The first true break took place on the July Fourth weekend.

Some of the Test Participants at Dahlgren. Left to right: Tom Doran, Rudy Griffith, Paul Lefeave, Larry Jackson, Dan Taylor, William “Gunner” Henderson, Mitch DeShazo, Richard “Red” Elmore, and Gene Loving.

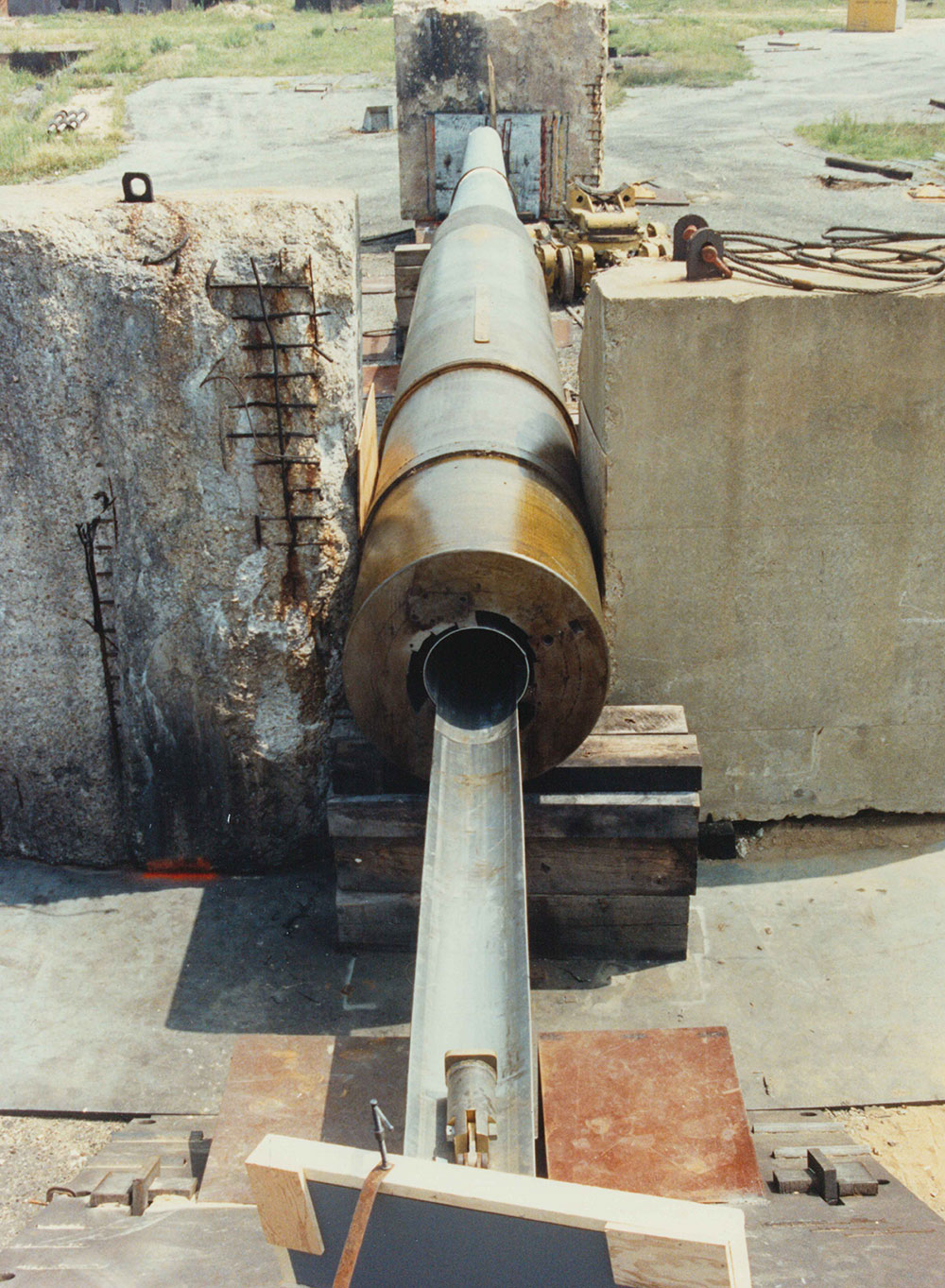

One of the test series conducted by Mr. Lefeave was designed to determine where in the open chamber the explosion occurred. Due to the destructive nature of this test event, it was determined this series of tests needed to be conducted in an isolated area of NSWCDD. Terminal Range Facility was chosen because there were no populated buildings within a half-mile of the facility. Preparations for this test series were a major undertaking due to the weight of the 16" barrel needed to conduct these tests and there was no 16" barrel available at Terminal Range. Thankfully, NSWCDD still had the railroad system in place in the late 1980s that connected all the range facilities, and the base still had its massive railroad cranes that could lift up to 350 tons. This enabled placing a 250,000 pound 16"/50 caliber barrel to be placed at Terminal Range. Also due to the destructive nature of this test, the barrel was placed on blocks on the ground instead of one of the two 16" gun mounts available.

Cranes Positioning a 16" Barrel at Terminal Range

Side View (left) and Top View (right), Open Breech Test Setup

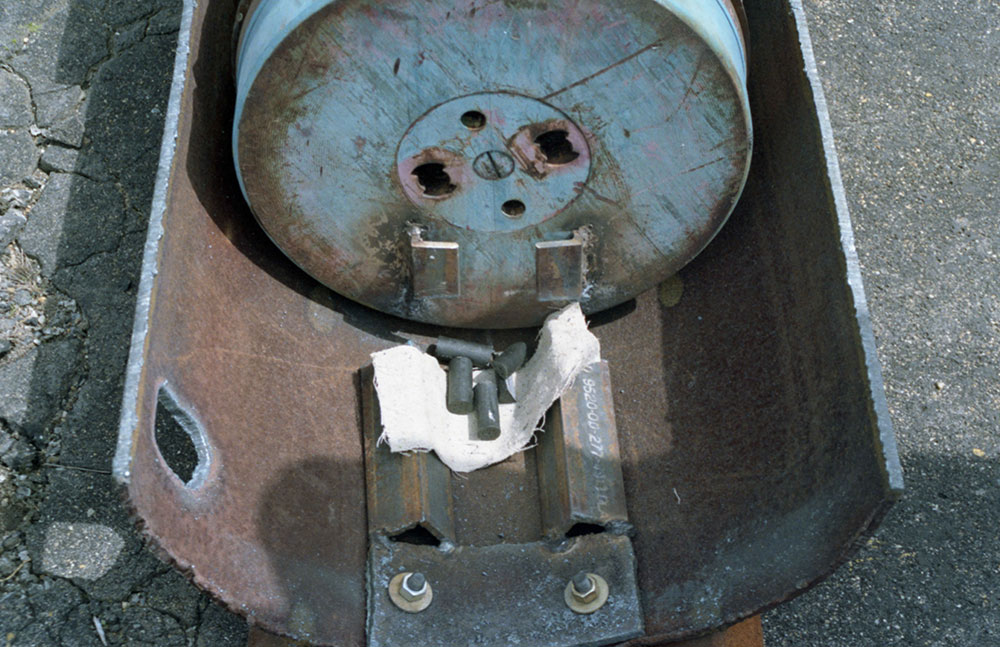

For each event, approximately 600 lbs. of propellant were ignited at various locations in the chamber until the explosion was replicated. In some cases, the propellant bags were statically placed inside the chamber and ignited electrically, while during other events, the propellant bags were rammed into the chamber using the USS Iowa’s Turret 2 Gun 2 rammer motor, then ignited electrically. It was determined the explosion originated between the two propellant bags closest to the projectile. During each test, the ignition of the propellant bags caused a similar reaction to the USS Iowa where the projectile moved up the barrel 5–15' and stopped, plus unburned propellant was thrown out the open breech. Following each test event, test personnel collected all the unburned propellant grains thrown throughout Terminal Range, and the explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) team was called to remove the projectile from the barrel. The removal of the projectile was a test within a test. The projectile was removed by a process called a “water hammer” or “water jack.” To perform this projectile extraction, ensuring the barrel could be used for the next test event, the muzzle was raised approximately 15' onto a concrete block then filled with water. The EOD team then slid a C4 explosive charge partially down the barrel, then capped the barrel. Once the C4 was ignited the cap momentarily held the water in the barrel long enough to build pressure needed to expel the projectile out of the gun’s breech.

Setup for EOD’s Projectile Extraction (Side View)

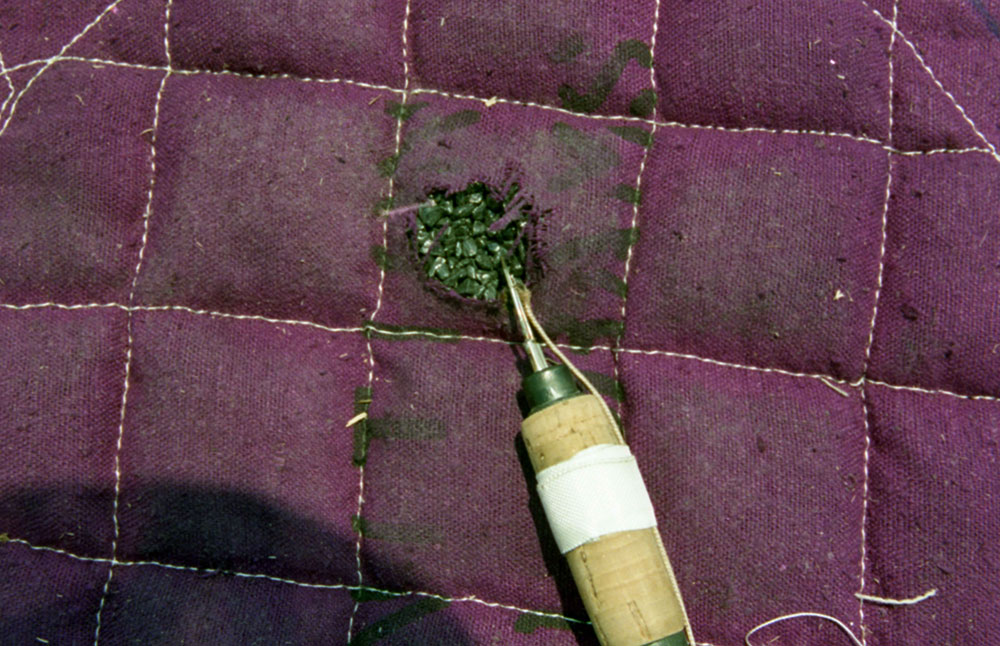

C4 Explosive Charge Mounted in Styrofoam used During Early Projectile Extractions

During the first extraction event, three attempts were required to extract the projectile from the barrel. After each attempt, the EOD team increased the amount of C4 explosive. During the third attempt, the projectile exited the barrel at higher than expected velocity, resulting in the projectile impacting the top of the thick concrete wall 300' behind Terminal Range, then ricocheting into the swamp another 300' beyond the wall where the inert projectile still remains today. The EOD team was able to fine-tune the extraction process and this method was used to remove all future projectiles from the barrel without incident.

Left: Post-projectile Extraction (Front). Right: Post-projectile Extraction (Normal)

Terminal Range (left) and Projectile Impact on Wall Behind Terminal Range (right) after First Projectile Extraction Event

Another notable event that happened during one of the 27 open breech test events was when the rammer head—used to ram the propellant bags into the barrel—was thrown nearly 3000' away from the test area after impacting the housing that protected the rammer motor from the explosive reaction created during each test. Test personnel searched the immediate area around the facility following the test event and could not find the rammer head. The next morning, Range Control received a call from the incinerator operator to inform them a large chunk of brass was found outside Building 1350 (located near the curve in the road that leads to B Gate). It was discovered that the brass rammer head went through the roof of the incinerator building and out the side. Fortunately, the incinerator operator left at 1500 that day—the test event occurred at 1505. One thing that can be proudly stated is there may have been a couple of incidents that did occur that caused some property damage, but no one, over two years and 4000-plus tests, was injured as a result of the test events at Dahlgren.

Entrance and Exit Hole Damage to Building 1530

Rammer Head that Impacted Building 1350

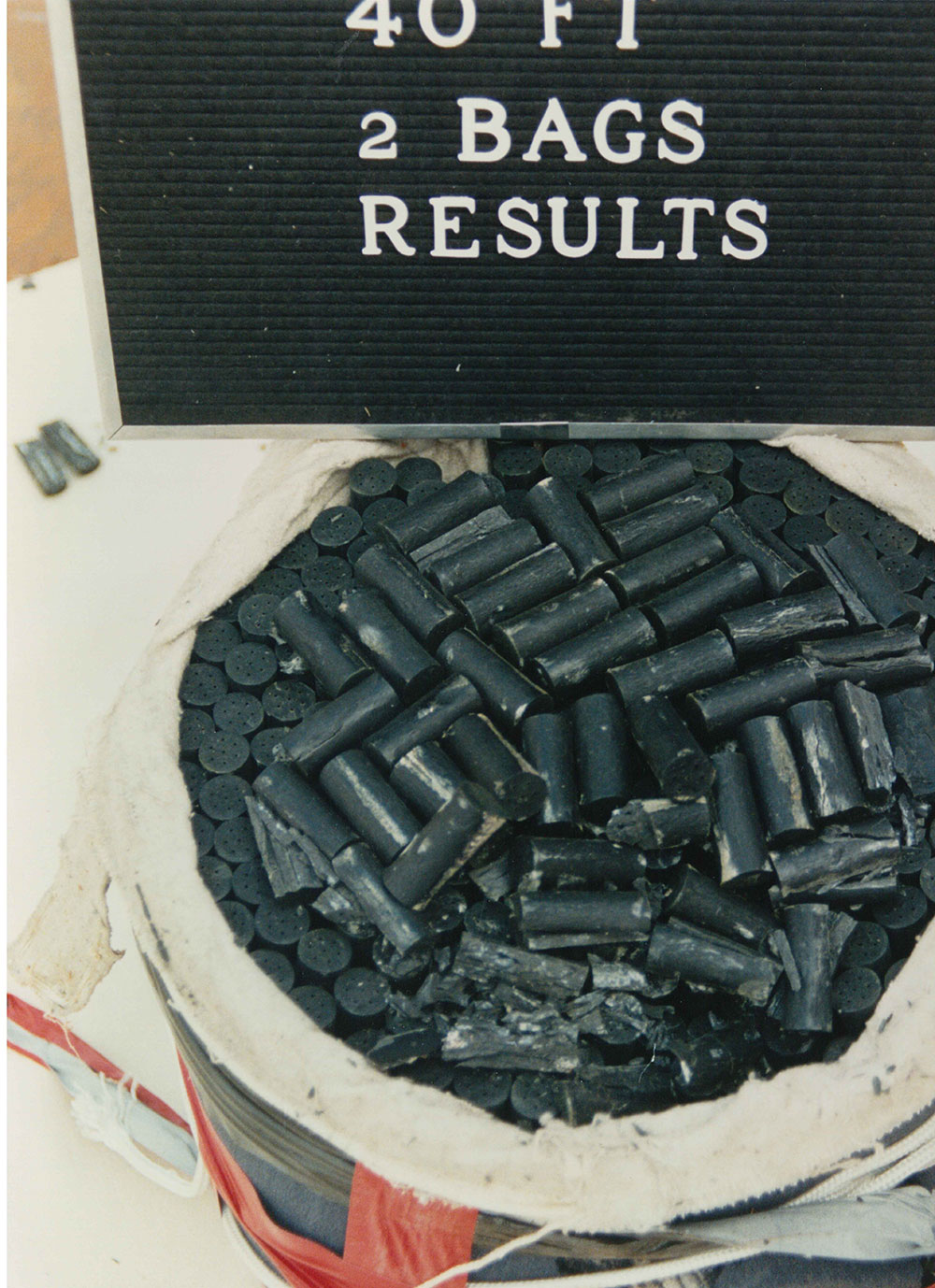

The Dahlgren test team also conducted numerous tests to evaluate the stability of the propellant grains and black powder ignition bags. The team conducted tests that crushed the propellant grains by running projectiles over them, exposed the propellant to static electricity and heat sources, fired primers into propellant grains, impacted the propellant grains and black powder pads with various gun tools, rammed the propellant bags at various speeds and force, and lots of “out-of-the-box” experiments to get the propellant grains or black powder pads to ignite. The team learned the propellant produced over 40 years before the explosion occurred was very stable and resistant to all sorts of abuse.

Propelling Charge Over Ram Results

40’ Drop Test Results

Propellant Grain Crush Test

Friction Test on Lathe

Heat Test

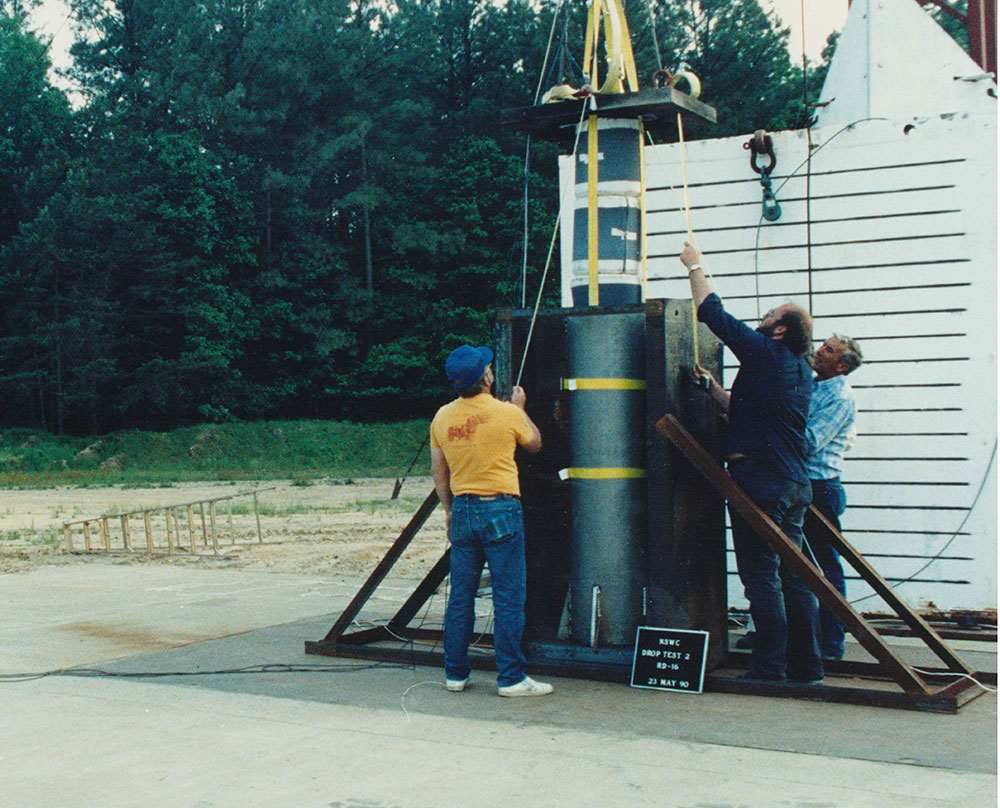

Working with Sandia National Laboratories during the second year of the investigation, the testing shifted from the gun to a series of drop test events that simulated over-ramming the propellant charges into a chamber. These tests occurred at the Experimental Explosive Area, also at the direction of Mr. Lefeave. After several drop test events, it was determined the propellant charge could be ignited if the propellant bag contained a small number of individual propellant grains laying sideways on top (tare layer) of the eight stacked propellant layers of the propellant bag, and the propellant charge was dropped from a height that simulated ramming the propellant charge at a higher than recommended velocity. This was the closing event to the USS Iowa investigation fault tree. Dahlgren testing was able to replicate the event that occurred in Gun 2 of Turret 2 and determine the probability of occurrence.

Setup for Drop Test Event (L-R; Gene Loving, Paul Lefeave, and Jim Satterwhite)

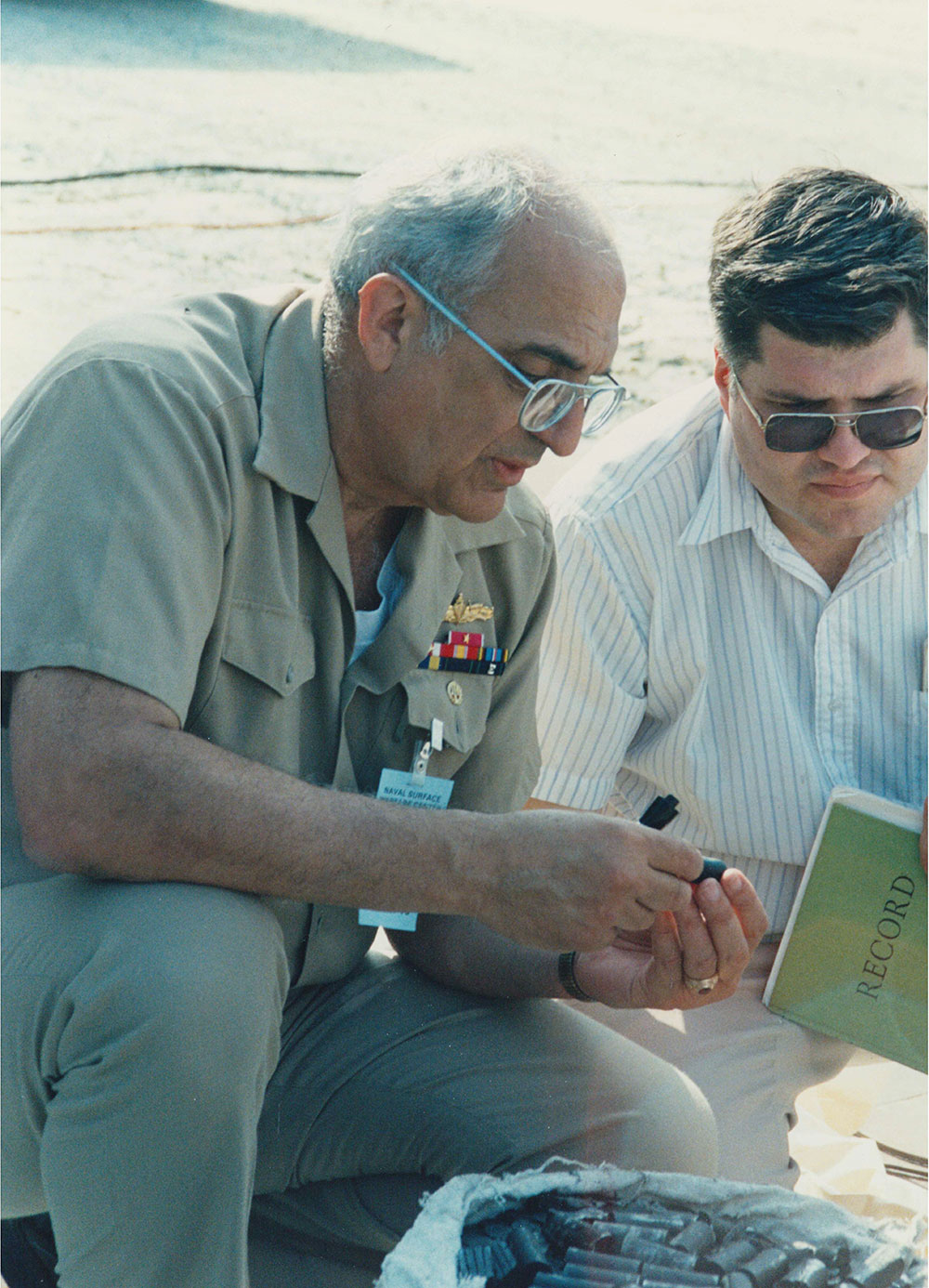

Post-drop Inspection (L-R; Steve Mitchell, Tom Doran, VK Davis, CAPT Miceli, Paul Lefeave, and Mike Fitzgerald)

CAPT Miceli and Sam Burnley Conduct Post-drop Inspection

The relentless pace of testing, test data analysis, and test reporting went on for months. It is a compliment to all Dahlgren personnel who worked diligently during this investigation to determine the root cause of the malfunction so that the battleship guns could be returned to service. While most of the direct support came from within G Dept., it must be noted Supply, Public Works, EOD, Security, Safety, and numerous other organizations and personnel provided whatever was needed, quickly and efficiently. It is estimated that over 2000 individuals who worked at Dahlgren from 1989–1990 assisted in this investigation. It would not have been possible for G Dept. to successfully complete testing at this rapid pace without the unwavering support of all of Dahlgren.

It was a very difficult time, but everyone was committed to finding what had caused the loss of 47 sailors. The team felt a strong obligation to the families to find out what had happened and how to prevent such an event from ever happening again. The 16" guns were returned to service and were used in the Gulf War a few years later.

USS Iowa was decommissioned on 26 October 1990 and is currently on display as a museum in Los Angeles, CA, where she recently celebrated 75 years since her initial commissioning on 24 February 1943. All the other battleships have since retired and are museums for the general public to see their greatness. Although these ships may be retired, the memory of the 47 sailors who gave their lives in service to our country must never be forgotten.

USS Iowa Museum, 22 February 2014.

Photographer: Jonathan Williams, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.