John Dahlgren - "The Father of Naval Ordnance"

October 16, 2017

To kick off our centennial blog series, it seems appropriate to begin with a short biography of our namesake, John Adolphus Bernard Dahlgren. He is chiefly remembered today as the “Father of Naval Ordnance,” and certainly his contributions in that field were his greatest achievements. Dahlgren’s story begins with his father, Bernhard Ullrik Dahlgren. Born in Sweden, Bernhard fled his native land after “authorities caught him handing out pamphlets that advocated republican principles.” Bernhard married Martha Rowan after his arrival in the United States and he began working as a merchant in Philadelphia. There, John Dahlgren was born on November 13, 1809.

|

|

The Philadelphia Wharves in 1829,

photo from Library of Congress

|

John Dahlgren’s decision to join the Navy came from outside influences resulting from his childhood in the major port city. The Dahlgren family resided near the wharves, and the daily mercantile traffic of ships attracted Dahlgren’s attention as he grew. In addition, he wrote that the navy yard “was not beyond the limits of a holiday ramble… More than one of my schoolmates, also, had passed from his place in the class to the quarterdeck; and Cooper had captivated my imagination.” Bernhard Dahlgren died in July 1824, leaving fifteen-year-old John, the oldest of five siblings, to begin his own career.

Dahlgren applied for admission to the Navy as a midshipman in 1825, not only to secure his social and financial status but also to pursue a personal goal “to win glory and achieve immortal fame.” Unfortunately, his application was denied. On March 28, 1825, he joined the crew of the merchant ship Mary Beckett and set sail for Cuba. The cruise went badly and he returned to Philadelphia on June 18.

However disappointing Dahlgren’s few months aboard Mary Beckett may have been, the experience gained was enough to secure his entrance to the Navy. On February 1, 1826, he was appointed to a midshipman’s position aboard USS Macedonian at the age of 16. It was no doubt a trying time for him. Midshipmen ordinarily received a warrant at the end of a six-month unpaid apprenticeship, but Dahlgren was not able to receive it until his return to the United States and remained unpaid for the entirety of the cruise. Additionally, much of the crew, including John Dahlgren, was taken ill with smallpox.

|

A diagram resulting from the survey of Connecticut and Long Island to which John Dahlgren contributed in 1834

|

That illness was the first of several serious medical issues that interrupted his career. Dahlgren’s illnesses prevented him from serving aboard a ship, so when he returned to active duty, he received orders to join the United States Coast Survey in Connecticut. His assignment to the Coast Survey was a practical application of “"is mathematical ability” that allowed him to excel and catch the attention of high ranking officials. His accomplishments on the Coast Survey included “becoming a second assistant in the survey and head of a triangulation party—the first naval officer ever to hold such positions."

However, his eyesight deteriorated during his time in the Coast Survey due to a disease of the optic nerve. Dahlgren and the superintendent of the Survey, Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler, felt that "his eyesight had become impaired by exposure in the performance of his duties in the Survey." As a result, Dahlgren took a leave of absence in November and sought treatment in France. The treatment was somewhat effective, but he returned in May 1838 with his eyesight still compromised.

Upon returning he married Mary Clement Bunker on January 8, 1839. Still seeking a cure, a navy surgeon advised him "to try the bracing effect of country life." In a paradoxical move for a seaman, he purchased a farm in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and worked it for several years. Once adequately recovered, he returned to active duty in May 1842.

Returning to duty was a turning point in John Dahlgren’s life. The first 17 years of his service were notable and established him as a man of determination in the face of adversity. However, he had yet to apply that determination to the developments in naval ordnance that he is remembered for today. That all changed with his assignment to USS Cumberland in 1843.

The Cumberland sailed for the Mediterranean from Boston in November. Dahlgren was then a lieutenant, in charge of four Paixhain shell guns. Biographer Ralph Earle noted that "it was here his bent for ordnance first came to notice." He realized the guns were difficult to sight and invented a new method for sighting them accurately.

The Mexican-American War exposed other problems with naval ordnance for which John Dahlgren developed solutions. He was involved in several major projects concerning ordnance during the war, all stemming from his assignment to the Washington Navy Yard. He was unimpressed with the Navy Yard’s facilities to produce and test ordnance and "received permission to build an ordnance workshop." He also was assigned to sight and range 32-pound guns. No range was available, so, “Instead of land he decided to use the Anacostia river for his range…. To determine distances, Dahlgren could use the techniques of triangulation he mastered under Hassler’s watchful eye.”

|

|

One of the boat howitzers designed by John Dahlgren

picture from Dahlgren's Boat Armament of the U.S. Navy

|

In the war, "Navy commanders found themselves engaged with a nation which had no fleet. Instead the Americans were faced with miles of

coastline protected by shallow waters" and the guns made for ship-to-ship combat were rendered useless. Dahlgren’s solution was to develop boat howitzers. Biographer David K. Allison wrote that Dahlgren’s “broader goal was a system of guns for all Navy ships that would give the fleet the most effective possible mix of weapons.” The boat howitzers were widely implemented and proved useful in the Civil War.

The boat howitzers and test range alone would have been great accomplishments, but John Dahlgren is most well-known for a more substantial contribution: the Dahlgren Gun. During his testing of the 32-pounders, he noticed potential improvements to prevent the gun from bursting at the breech. It was a danger that became too real for him in November 1849 when he was standing near one that burst, killing the gunner and throwing a 2,000-pound piece of the breech in Dahlgren’s direction. Soon after, he designed a gun that redistributed the metal, making it safer for the gun crew to operate. He submitted plans for 9- and 11-inch models at the beginning of 1850 and "personally won support for their implementation both within the Navy and in Congress." The 9-inch model was first used on Merrimac-class frigates in 1856, and the guns were nicknamed "soda bottle" guns because of their distinctive shape.

|

| An 11-inch Dahlgren gun |

The beginning of the Civil War led to promotion potential for John Dahlgren; then-commander of the Washington Navy Yard resigned to join the Confederacy, leaving Dahlgren the "most senior officer assigned to the yard who did not ‘go South." In that post he designed a 15-inch gun, which the Navy requested for use against armored ships (one of which was USS Merrimac, captured by the Confederates and remade as CSS Virginia), but which Dahlgren himself objected to, thinking it too dangerous to use.

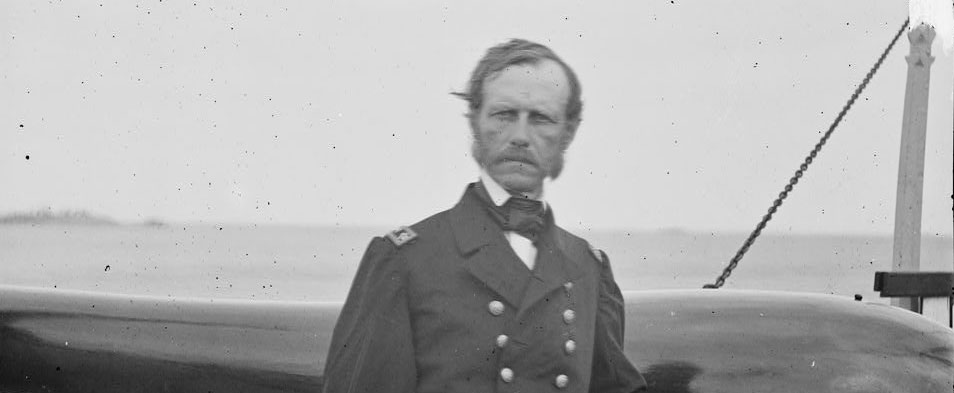

Opportunities continued to increase for him and in July 1862 he was made Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance where, "his responsibilities fell into three broad categories: developing weapons, testing weapons and inventions, and supplying the fleet with ordnance and related materials." However, his time at the Bureau of Ordnance was short-lived. He sought a command with the South Atlantic Squadron in Charleston at the beginning of 1863, but his request was denied. His widely successful ordnance development meant that "Dahlgren’s reputation with officers of the Navy was that of a scientist rather than that of a sailor and fighter." However, President Lincoln pressured the Secretary of the Navy to give Dahlgren the command, and he assumed it on June 24. He made several unsuccessful attacks on Charleston in 1863, which were a significant blow to his reputation, and "even before the war ended, he was defending his actions to Congress. Justifying his conduct and defending his reputation would remain major preoccupations until his death." He remained in command and assisted in the fall of Charleston in 1864, but still faced criticism.

|

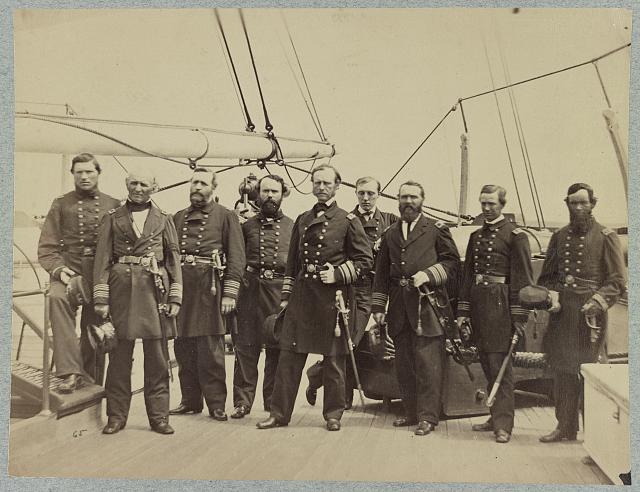

| Dahlgren and his staff on board the U.S.S Pawnee in Charleston Harbor, photo from the Library of Congress |

After the war, Dahlgren married Madeleine Vinton (his first wife, Mary, died in 1855) and was assigned to command the South Pacific Squadron. He held the post from the end of 1866 until mid-1868. Dahlgren’s time there was "uneventful, given over largely to the domestic life that he and his family were able to pursue."

He became Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance again after leaving the South Pacific Squadron, but faced the implication from a report of the Joint Committee on Ordnance that competition between him and other officers "prevented fair competitive trials of the various devices and systems advocated by each," essentially preventing further innovation. He resigned his post for command of the Washington Navy Yard on August 10, 1869, dispirited by the report.

John Dahlgren died rather suddenly on July 12, 1870, after suffering chest pains. He is buried in Laurel Hill cemetery in Philadelphia. His accomplishments ultimately eclipsed his late controversies because, "his Dahlgren guns… became the standard armament for the frigates of the United States Navy."