On 2 August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait, triggering the Gulf War. Dahlgren scientists and engineers were once again called upon to meet wartime needs. Today’s blog, taken in part from an article written in 1991, describes one such way that Dahlgren supported the warfighter.

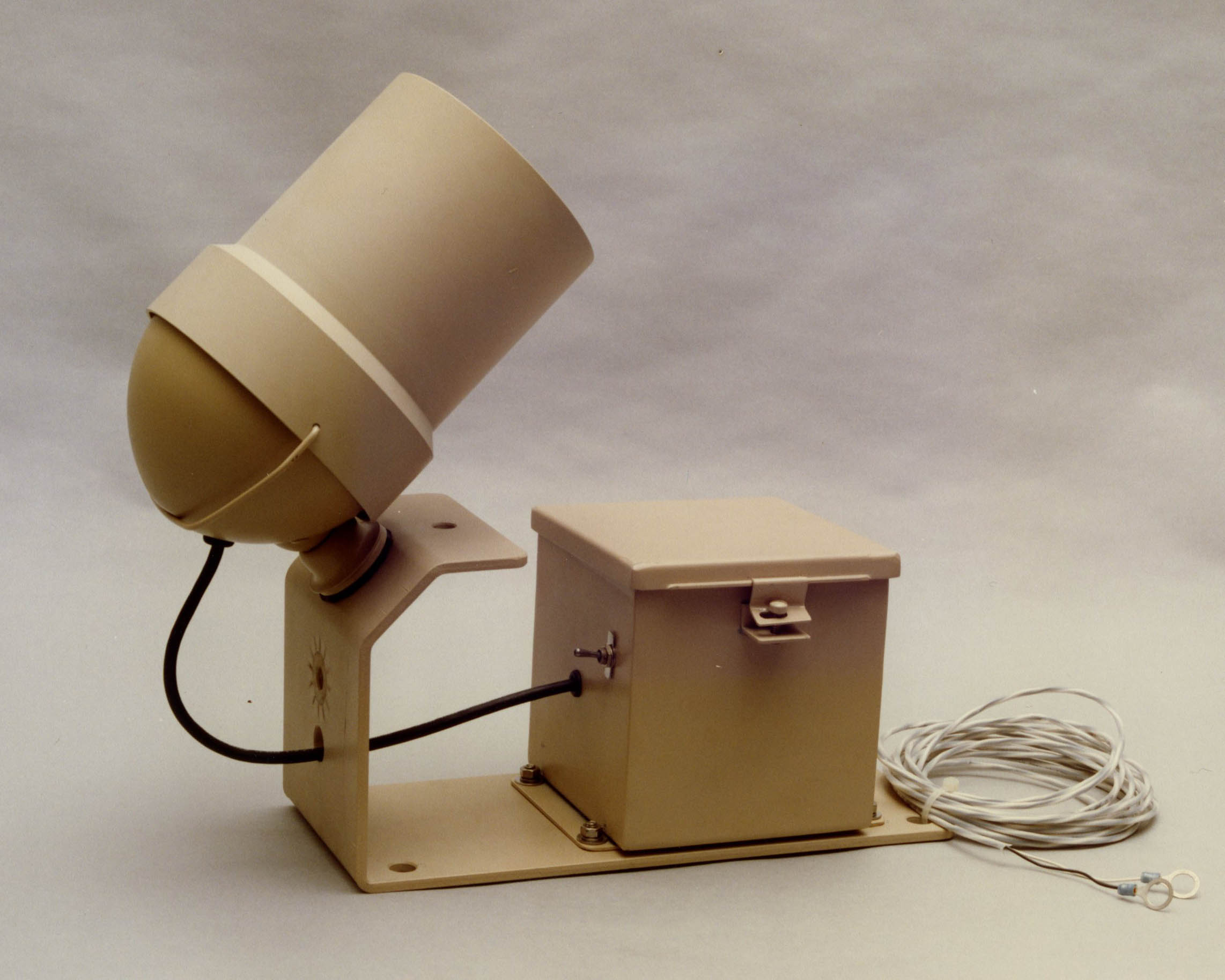

If you’re interested in seeing an IFF in person, check out the one at the Dahlgren Heritage Museum.

Naval Surface Warfare Center Comes to Aid of Marines in Gulf

By Doug Davant

There is a uniquely American standard, best often observed in wartime. It goes: “The tougher the challenge, the tougher the effort!”

It all began the second week of Operation Desert Storm, when U.S. Marines were leaning on the precipice of the ground offensive. The Marines had recently suffered casualties while backing coalition forces in wresting away a small Saudi village from Iraqi invaders. Tragically, in what became known as the Battle of Kafji, most of those casualties occurred because of “friendly fire.”

For allied military planners, keeping loss of life to a minimum was an often stated objective; even Iraqi life was considered a part of that goal. So friendly fire tragedies, although an inevitable consequence of war, were unacceptable. Accordingly, as the ground war for the liberation of Kuwait was nearing a countdown to proceed, coalition forces were ordered to paint an upside down “V” on all vehicles to help distinguish them from the enemy’s. But the Marines, who would be leading those forces into the heart of the fighting at Kuwait City, wanted something more. And they wanted it fast.

A convoy of U.S. Marine armored personnel carriers head south from Kuwait City toward Saudi Arabia, part of the initial withdrawal of allied troops from the nation liberated from Iraqi forces. The Marine vehicle shown holds an IFF unit.

On Feb. 2, NAVSWC was handed an urgent request from the U.S. Marine Corps center for Amphibious Warfare Technology (AWT) at Marine Corps Base Quantico to develop such a device. W. S. “Bill” Furchak, head of the CW Shipboard Systems Branch (H33), remembers getting the phone call at his home “late Saturday evening...”

“…They (AWT) said they had several urgent issues that the troops in the field needed resolution on right away.” Furchak said, “Basically, I was given a timeframe of about two weeks to define the problem, come up with solutions, evolve hardware to ship out to the field and get it installed.”

Despite the demand for problem analysis, solution philosophy, researching, designing, engineering, ordering of parts, assembling, testing, and final development of a piece of equipment from scratch in just two weeks—unheard of in civilian defense contractor circles if not impossible—Furchak felt it could be done.

“We set up a meeting early the next morning (Sunday) at Dahlgren. We had CAPT Tom Manley, the PM (program manager) from AWT, and I called in (William E.) ‘Bill’ Blakely and other people around the center who would have expertise, specifically Roger Horman of F44, in what I felt would be the area of concern. So, at that meeting AWT scoped out in more detail just what the problem was…we even called the field in Saudi Arabia for clarification.”

Furchak said there was another meeting the next day at Quantico where the problem was further defined and all options were explored.

“A final decision was reached late that night as to what option we would take,” he said. “Early Tuesday morning (Feb. 5) we actually started with the design effort.”

Tasked to lead the design effort were H33’s Eric Stevens and Monty Pugh. Immediately they got to work, realizing there would be plenty of engineering hurdles along the way to leap. Significant among them was the power demand for the equipment and its associated electronic components. Pugh and Stevens recognized that the most commonly available parts are associated with either the automobile industry’s 12-volt DC system or 110-volt, 60-cycle household current. But this project called for parts associated with military-related 24-volt DC systems and those parts are often in short supply; shorter still considering an ongoing war eating into the rare availability.

“In some cases we had to design while talking on the phone with the vendors… I had a standard question: ‘if you don’t have the part that I need, what’s the closest you can come to it?’” Pugh said. Working long hours, Pugh and Stevens, together with Blakely, finalized a design by Friday afternoon.

The next major hurdle was to procure thousands of electronic and hardware components needed in the span of just one work week. So that same Friday afternoon, Pugh and Furchak along with H04’s C. L. “Charlie” Hill, met with Connie Grittner (S13) and S18’s Richard K. “Buddy” Payne to ask the impossible. The reply was: “can do!”

“Considering we didn’t provide them our requirement until 2 p.m. Friday, by close of business that day every item we requested was ordered and immediate deliveries were negotiated. We began receiving items the next morning,” Furchak said.

Meanwhile, on Friday, Pugh went to E Department’s Engineering Prototype Branch, E14, and the Electronics Development Branch, E13, for help to assist with the part of the design they could not procure and to assemble the final system. The work phase had passed its revving up period; it now shifted into high gear.

John P. Cullen, E14 branch head, explains what happened next. “We got a sketch on Feb. 8th, about 2:30 in the afternoon,” he said, holding up the original draft, which showed the oil-stained effects of spending time in a machine shop. “Of course Monty needed a prototype built in a hurry from the rough sketch… but not all of the necessary material was available so we had to search around and make a selection.”

As the Friday sun was setting, Cullen said that Loyd D. Hendrix of E14 was able to dig up a truck and drive to Baltimore to hopefully get the material from a source that had not yet shut its doors for the weekend. A crew from E14, Donald M. Boone, Mike Wade, and Earnest W. Wilson joined Pugh to begin work on Saturday morning manufacturing a multipurpose prototype bracket to mount the device.

“When Monty showed up Saturday, he had another material needed—a shroud,” said Cullen. “I noticed that this was going to be the critical item, in terms of material availability and time to fabricate. So I called (E14’s) Gary Allensworth and suggested that he get some people in on Sunday to standby for work.”

Allensworth brought in Darryl Matthews, Alan Schwarting, and Gary A. Burcham to confer with Pugh at Dahlgren. They drew out a sketch and, after fabricating three prototypes from Pugh’s verbal directions and inspection, faxed it to Cullen seeking both agreement with the shroud design and material to begin manufacture. After design concurrence was finalized, it was determined that just enough material was available to get started.

Time being crucial, shop manager John Steward and his workers in E14 sought ways to streamline the shroud fabrication. Using CNC (computer lathe) equipment they refined a method whereby a shroud could be produced in 10 minutes. But, to make the industrial engineering feat work, a constant source of material had to be maintained. Urgent calls revealed a Philadelphia source for the material; again there was a need to leapfrog the long supply chain and take a truck ride on I-95 north. After the functionary dictates of supply regulations were met and three price quotes obtained, and with the help of a driver from W dept., E14’s Wes Alexander made the trip to take care of the paperwork.

Manufacturing a bracket, power supply box, and shroud, however, were only part of the process. Precise painting requirements, to meet specifications of the non-reflective buff demand of desert combat, were still looming ahead, let alone any testing of the finished product.

“We had the public works shops at White Oak and Dahlgren working with a special latex paint that one of my people located over the weekend so that Monday morning we could go buy it,” Cullen said, “But we still had some problems with the surface preparation that caused the paint not to adhere well. So we had to work around that and make some changes… all the surfaces had to be either iridited or glass-beaded; then, after a powder paint was applied, it was glass-beaded again to dull it up so it absolutely would not reflect light.

“And at one point we ran low on powder paint… we had to locate more so one of the guys in the composite shop, (E14) Robert Lam, I believe it was, located a source of this powder paint through the manufacturer. The manufacturer told us of a certain company in Baltimore that had some… I don’t know if that company was a distributor or just had some paint on hand, but they met our plane at BWI and helped fill a crucial need to be flown back to Dahlgren.”

As the sun set on Feb. 12th everything was coming together. The project tasks now only required electronic fabrication, final assembly, checkout, and packaging. Then a snag snarled the process.

H33 had received all the parts ordered through S department but, according to Furchak, “there were two ‘not so minor’ problems. Two of the critical systems electronic components received were not as ordered,” he explained. “With no time to order and have new components manufactured in only three days left, Eric (Stevens) and Monty (Pugh) discussed the problems with the vendor’s engineering staff to resolve the problem.

“On one item, the vendor flew an engineer out that day with all the pieces to modify the electronic components we had on hand. But when he arrived, Eric and Monty realized the vendor’s engineer was going to need help (with the modification) so they called back (the team of) H33’s Diane LaMoy and Skip Lowe and four people from E13 to assist with the job. This team worked through the night and on through to Friday evening to complete the task.”

But the effort just solved one of the critical needs. “The other item was modified at the vendor’s plant on the Eastern Shore of Maryland,” Furchak said, “The vendor had arranged to ship the components with one of his trucks late Friday night.”

It was to be later than anyone expected, however. “I got a call about 6:30 p.m. on Friday from the driver,” Furchak explained. “He got about 50 miles from his plant and his engine blew up.”

Furchak told the driver to “sit tight” then sought a volunteer to meet the stranded driver. “Bob Fitzgerald (H33), who was helping finish up the other components for E13 assembly, jumped into his car and drove to Easton, Md.—100 miles from Dahlgren—and across the Bay Bridge to pick up the items,” Furchak said. “He returned around 11 p.m. Friday (15th) and immediately delivered the items to E13 to assembly the final units.

With tasks shifted to E13 so was the spirit of urgency, according to E10’s Johnny W. Walters. “I’ve never seen anything like it in the 20 years I’ve been here,” he remarked. “People just turned-to and worked their rear ends off… nobody wanted to go home. I saw people work sick, people work tired, people work long hours. It was incredible.

“When you think of our high tech victory in the Persian Gulf, you think of big programs like Patriot and Tomahawk systems as being the ‘heroes’. But the smaller programs count plenty. After all, Patriot and Tomahawk have been in development by civilian defense contractors for more than a decade. This program began from scratch and was completed in two weeks!”

Cullen said the same analysis applied to E14. “Everybody involved took on a ‘can do’ attitude, there was never any defeatist feeling about the difficulty of the work. But we used almost all of our resources. We had to have 100 people involved at both sites to make sure the job was done on time.”

Cullen also credited supply, materials public works, munitions, transportation, and public works along with his people to get the job out. Furchak added two more groups to that list. “From the beginning, F22 and F44 supported us in testing the ‘quick fix’ system and prototype, and an effort to look for a long term solution we knew would eventually be needed,” he said. “Tim Jaynes (F22) and Bela Vastag (F44) led their branch’s team efforts to support H33, which began from day one to help define technology options, and conduct and analyze testing of candidates for possible long term development.

“In one test in particular, the Marines at Quantico flew in a helicopter from HMX-1 (the Presidential squadron) to pick up F22, F44 and H33 test team personnel for a test at Langley Air Force Base. It was F22’s and F44’s efforts that validated the functional capability of the immediate system we deployed and set the stage for the center to take the lead for the follow-on research and development.”

Meanwhile, the effort at E13 focused on completing the units in just three days. However, the kind of material shortages that plagued E14 didn’t go away when the job came into the next shop. The order called for 350 units but just 310 units could be outfitted with the electronic components that vendors had supplied. E13 would have to make do with what it had.

The workaround efforts moved through the week. It was Friday, Feb. 15th, 5 p.m. It was time when most of the center’s shops and office personnel were heading out the gate to begin their three-day-long President’s holiday. But at E13 and H33 the work continued.

“They were working all that afternoon,” said Walters. “They worked that night and in to the next morning.”

Finally, at 2 a.m., Saturday, the job was done—though the work wasn’t.

Blakely and Hugh received the finished units and formed the team to deliver the devices to the Marines in Saudi Arabia.

The ground war had not yet begun on that cold pre-dawn Saturday. President Bush had given Saddam Hussein a high noon deadline to pull his forces out of Kuwait in the hopes of averting it. If the Iraqi dictator heeded that call perhaps the units wouldn’t be needed. Despite all the hard work everyone prayed for that to happen.

Hussein, however, was sticking to his maniacal guns. So as the high noon deadline passed on Feb. 16, Blakely and Pugh were in the cargo bay of a Marine C-130 on the way to Rota, Spain, the first leg of their travel to Saudi Arabia.

Two days later (10 a.m., Monday, Saudi time) they landed. They were met by Carroll Childers, the NSAP (Naval Science Advisory Program) technical adviser on Gen Boomer’s staff in Saudi. Childers, who initiated and coordinated the project with AWT, had arranged for a CH-53 helicopter to meet Pugh, Blakely, and equipment, and rush them to the front lines—in actual view of the Kuwaiti border. There, as Blakely put it, “under nets in the middle of nowhere” and within sight and sound of Iraqi and allied artillery, NAVSWC’s project began to be consummated. “We began immediately, we hit the ground working,” he pointed out.

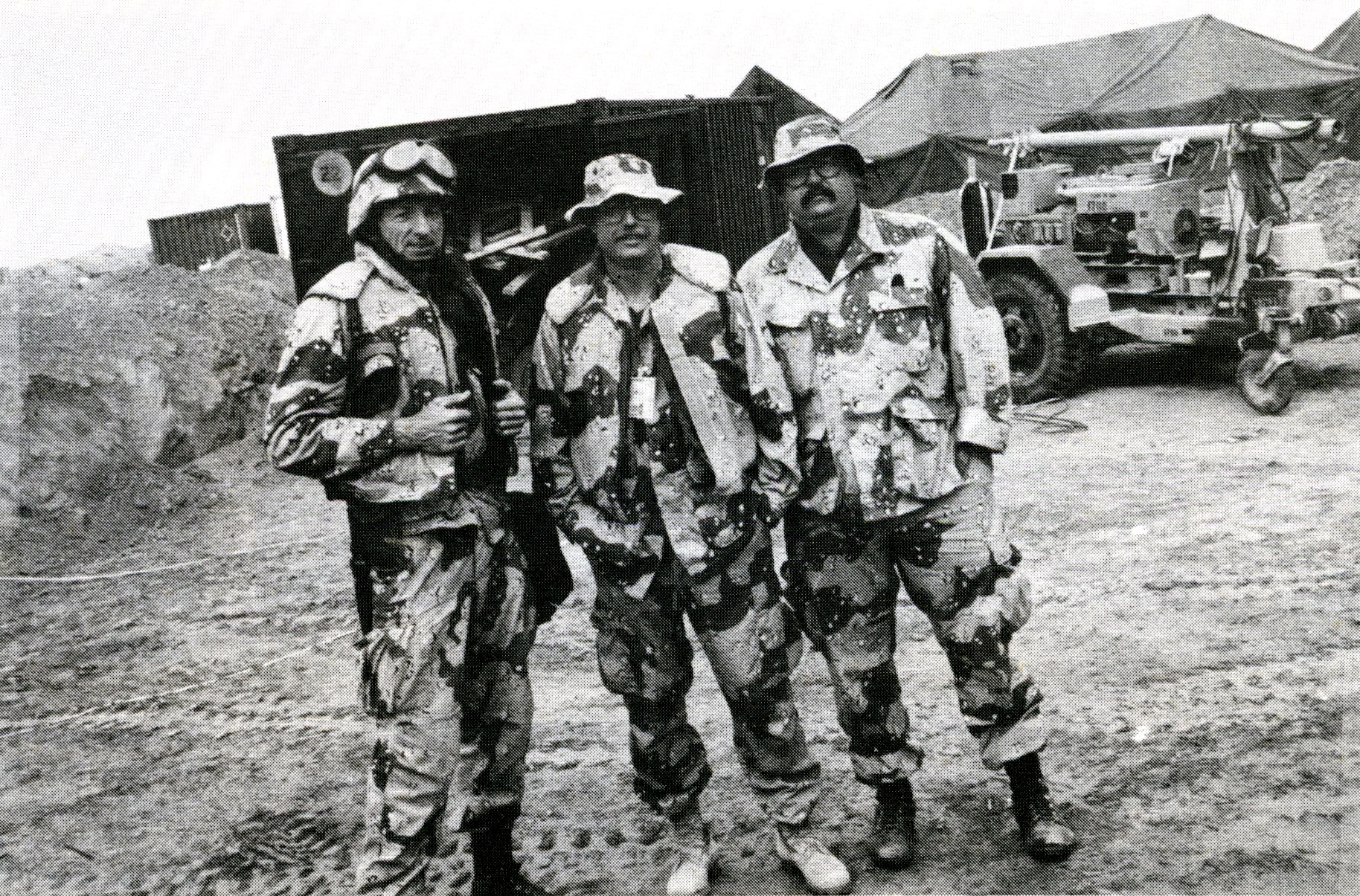

Left to right: Carroll Childers, NSAP Advisor for Marines in Saudi, stands with Monty Pugh and Bill Blakely in the Arabian desert near the Kuwaiti border.

But, also immediately, a new challenge arose—how to mount the E14 brackets on armor plate was one. “We knew we would be mounting on armor but the Marines told us it wasn’t tempered steel… we burned up three drill bits learning that wasn’t the case,” said Blakely.

Blakely, though, explained that they had prepared well for every eventuality. “We took along supplies for numerous mounting options,” he said. “We also used tape… anything to get the units mounted.”

Pugh said there was no time to do extensive “shake, rattle, and roll” tests, but he had experimented on mounting options with the unit on a LAV (Light Armored Vehicle) around the Dahlgren woods. The team also had to trust their knowledge about the materials used and faith in their design that the units would withstand fierce desert sand or rainstorms that could fill Arabian wadis.

Another problem to solve was how to get electrical power from the M-60 tanks, LAVs, Bradley Fighting Vehicles, and Humvees to the system. Obviously, drilling into the armor plate to draw on engine alternators was out of the question. Pugh had a solution. “I knew that most of the vehicles would have taillights,” he said. “It was a matter of taking off the light lens and tapping into the electrical system.”

Working furiously on the front lines with elements of the 1st and 2nd Marine division; eating MREs, grabbing few precious moments of sleep in vehicles chilled by the cold desert sands, having that sleep interrupted by the sound and fury of battle, they showed each tank and vehicle crew how to mount and operate the units. Pugh and Blakely moved among Marine units along the front almost as fast as the leathernecks would eventually move through Hussein’s army. Finally, NAVSWC’s work was over. Now Pugh, Blakely, and their coworkers back at the center waited anxiously. Would their hard work pay off?

That question would be answered hours later when the ground war campaign began, the very night they finished. However, the most definite answer was already given, according to Pugh. “Although I didn’t know it at the time, the very first group of Marines I worked with had been involved at Kafji. They were the group that had lost 11 buddies there. Needless to say, they were happy to see the system… they jumped on it right away. They dropped everything they were doing to get it installed. That’s how important they thought it was even though it was new to them!”

So new were the units that they weren’t officially named. There is no military nomenclature, like “Mk 23” or “AN/MAR-3” even. Thus far the best identification is: IFF system (for identification friend or foe). The “how” of the units’ functions can’t be disclosed. Its importance can’t be understated, though. It saved American lives. And, according to the personal report of Marine Corps field commander, Gen Boomer, its makers deserve the highest of praise.

The tougher the challenge, the tougher the effort!