Commander's Quarters

January 23, 2018

|

Ralph Earle, seated at his desk.

Courtesy of NHHC |

|

President Woodrow Wilson.

Courtesy NHHC. |

|

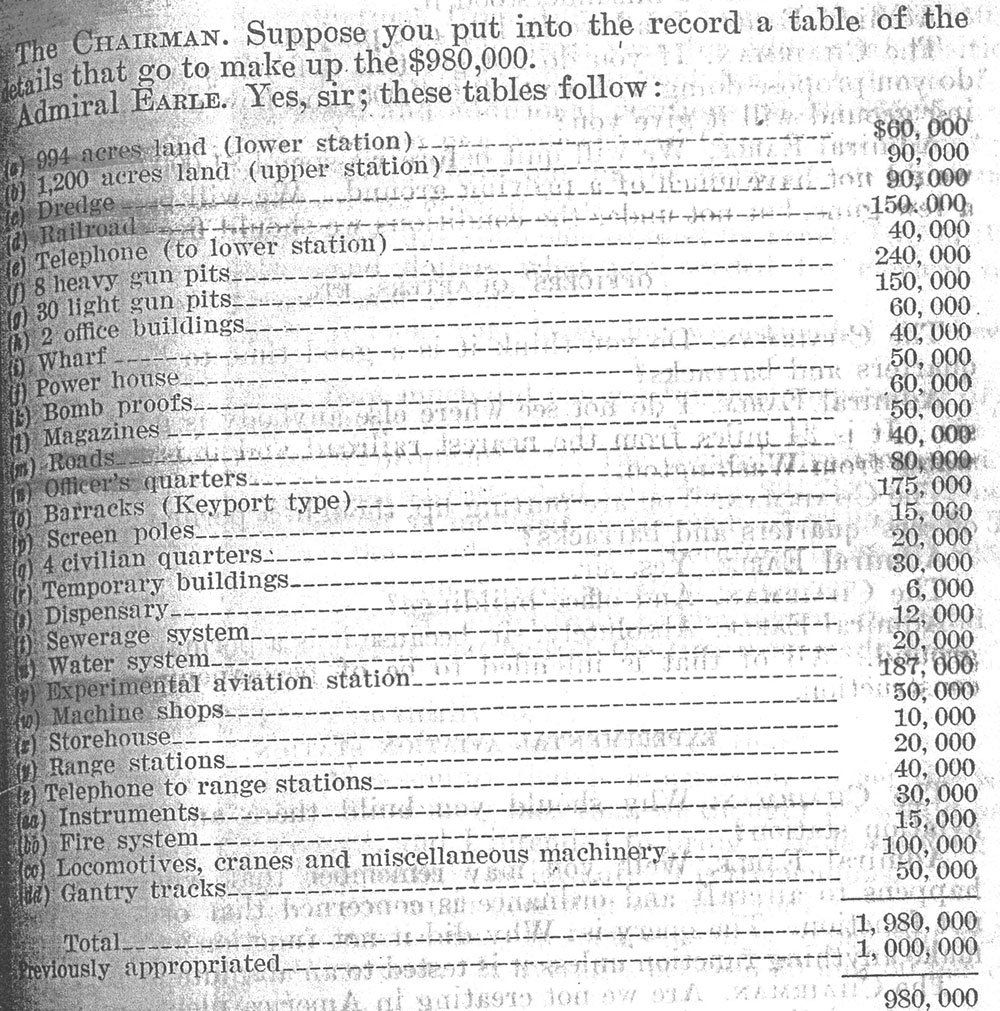

| The initial estimate that Earle presented the Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives |

If you haven't already done so, please read our previous blog post on the problems at Indian Head that led to the creation of Dahlgren. The blog can be found here.

This week's blog continues that story.

The American political landscape in 1918 was as contentious and partisan as it has ever been. The politics surrounding Dahlgren’s creation were particularly fierce, made up of unsubstantiated rumor, innuendo, and attempts at pork-barrel legislation. The United States was engaged in World War I, which had brought on expanded government spending. The military easily received and quickly spent large amounts of money with less justification than was ordinarily required. However, all that spending was done with one eye on peace.

Following safety and range problems at Indian Head, Bureau of Ordnance (BUORD) Chief RADM Ralph Earle ordered CDR Henry E. Lackey to select land for a new proving ground that would mitigate the issues. Around 1 January 1918, Lackey recommended the site that eventually became Dahlgren. On 8 January, President Woodrow Wilson presented his “Fourteen Points” to a Joint Session of Congress, outlining his personal opinions on the proper conditions for peace.

Just ten days later, Earle approached the Committee on Naval Affairs of the House of Representatives (CNAHR) for initial funding to create the new proving ground. The President’s Fourteen Points must have been a hard act for Earle to follow because disarmament was one of Wilson’s objectives. Earle requested $1M to purchase land and begin operating the new proving ground. He told committee members the original estimate for establishing the new proving ground was $2M, but he was restricted to $1M, saying “I cut everything down in order to bring it within the million.” Earle received appropriation from the 65th Congress to purchase the land and start building, but he also signed up the BUORD for a ferocious fight over Dahlgren’s existence that would play out in Congress over the next several years, intertwined with issues of peace and disarmament.

The money awarded for Dahlgren fell into a budgetary gray area for “necessary improvements at and maintenance of proving grounds,” which Earle first called a war measure but also said would be used to make permanent changes. The potential for confusion over the status of the new proving ground was compounded when Earle told the committee “We only intend to use [Dahlgren] for such guns as can not be safely tested at the present grounds,” and that Dahlgren was to be a detachment of Indian Head. These decisions meant the money was readily obtained in the budget for the fiscal year beginning 1 July 1918.

|

| The estimate that Earle submitted to the House Committee on Appropriations for deficiency appropriations. |

Although Earle received the money he requested, he still believed the whole project should be completed; he needed to double the funding. So on 4 October 1918, he approached the Subcommittee of the House Committee on Appropriations, then making deficiency appropriations. (Astute readers will recall that Dahlgren’s birthday is not until October 16, so the legislation creating the proving ground wasn’t passed yet. Dahlgren did not officially exist.) He told the committee that if the BUORD did not receive the deficiency appropriation, “We will quit before we spend $1,000,000 and we would not have much of a proving ground.” He presented the committee a version of the budget showing the need for an additional $980,000, including more permanent structures like officer’s quarters and office buildings, saying he intended to establish a permanent proving ground with permanent construction. The deficiency appropriation brought his total for the project to $1,980,000.

While Earle was trying to build quarters and offices, the war began to wind down and Dahlgren was swept up in larger political movements. On 25 October 25, President Wilson appealed to the American people to elect Democrats to Congress in the upcoming elections, a move that backfired because it was largely perceived as “a partisan maneuver which betrayed his own promise that politics should be adjourned until after the war had ended.” Republicans gained a 44-seat advantage in the House and a 2-seat advantage in the Senate, marking an ideological shift toward disarmament and isolationism. New and different Congressmen joined the CNAHR, and their policy objectives changed too.

The first hints the committee disapproved of the amount of money spent on Dahlgren came after the war ended, and the work of establishing a lasting peace began. Suddenly, any Congressional approval of money spent on a new proving ground carried with it an admission the Navy might need new guns in the future; that the peace might not last. Disarmament was one of the most important conditions for peace, appearing in Wilson’s Fourteen Points, the Treaty of Versailles—which would officially end the war—and the Covenant of the League of Nations. The League of Nations, in particular, called for “the reduction of national armaments to the lowest point consistent with national safety.”

Earle was called to speak to the CNAHR in early June 1919 about the BUORD budget for the next fiscal year. Understandably, committee members balked when Earle asked for $1,620,000 to fund normal operations at Indian Head and Dahlgren. The appropriation was much higher than what Indian Head had received before the war, and the next fiscal year was to mark the beginning of the transition back to a peacetime economy and continued demobilization. One of the members of the committee even went so far as to ask if Earle thought the League of Nations would not actually take place.

Earle’s response to the attacks on his estimated budget was a poetic defense of the BUORD. He said, “I could not reduce it and say that I was carrying out the work of the Navy. Anything that goes wrong on board ship comes right back to me, and the first thing that happens is the statement that I did not carry out the proving of a gun, that I did not fire the necessary number of rounds. Why? Because I did not have the money.” Political circumstances of the time also worked to Earle’s advantage. Although committee members seemed to object to the spending, they were also under pressure from Wilson to quickly pass bills that year and make way for consideration of the treaty. Earle got the money.

Construction at Dahlgren gradually progressed. Meanwhile, bitter contests continued in Congress, resulting in the rejection of the Treaty of Versailles, and with it, the League of Nations.

|

| Representative Sydney E. Mudd |

|

| Senator Ovington Weller |

|

The petition submitted to

Sens. Mud and Weller |

|

| Edwin Denby shown in October 1923 |

|

| Representative A.E.B. Stephens |

Republicans gained seats again in the 1920 congressional elections, resulting in a two-thirds majority in the House of Representatives. The party’s platform of the time argued that the Wilson administration “used legislation passed to meet the emergency of war to continue its arbitrary and inquisitorial control over the life of the people in the time of peace, and to carry confusion into industrial life.” They began to scour for military overreaches and excessive spending. Congressmen responsible for the budget were also accountable to their constituents. The politicians that spearheaded the attack against Dahlgren were from Maryland and were looking out for their state’s interests. Problems with Indian Head aside, many people were (or thought they would be) negatively impacted by moving operations to Dahlgren. A petition to halt the move to Dahlgren was signed by 456 people and submitted it to Rep. Sydney E. Mudd (R-Maryland) and Sen. Ovington E. Weller (R-Maryland). The petition repeated some widely held misconceptions about the transfer of work and the facilities at Dahlgren, implying it was a waste of money.

The petitioners got their wish. After taking office in the spring of 1921, the CNAHR sent a letter to the new Secretary of the Navy, Edwin Denby, inquiring about Dahlgren expenditures. Denby responded the total to date was $2,210,205.11 (equivalent to about $27.5M today), with over $60,000 going toward constructing and furnishing the commandant’s quarters. Subsequent hearings revealed the quarters were “the matter that brought the Dahlgren question to the attention of [the] committee.” Denby’s letter began the long Congressional fight to close Dahlgren.

A special committee was formed to investigate Dahlgren and Indian Head expenditures. There was cause to believe the BUORD had misled Congress in its request for appropriations, but the committee hearing was not so much an investigation as an attack on Dahlgren, spearheaded by CNAHR members Reps. Mudd and Ambrose Everett Burnside Stephens (R-Ohio). During hearings they seemed to be fishing for any evidence implicating the BUORD or Dahlgren.

Stephens reasonably questioned CDR E. H. Douglass of the Supply Corps about expenditures on the commander’s quarters, but the hearings also took some strange turns. According to James P. Rife and Rodney P. Carlisle, authors of The Sound of Freedom, several petitioners “argued … the old Indian Head proving ground was perfectly safe and that its location and facilities were unsurpassed for gun proofing. Conversely, Dahlgren was uneconomical and redundant in their view.” Their testimony, however, exposed they were not experts on the subject. A number of the signatories were brought before the committee and asked about the impact of the move on their personal lives. Even more oddly, in his statement, Richard Dement, then assistant to Indian Head’s powder expert, could not provide the committee any kind of expert testimony and found himself answering questions on rumors he had heard about Dahlgren, including the impact of Dahlgren on the crab and oyster industries.

Following the hearings, on August 24, Stephens introduced a Joint Resolution—the greatest threat Dahlgren had yet faced. “Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, that no part of any existing appropriation shall be obligated or expended for or on the naval reservation at Dahlgren, Virginia, or on any approach thereto by land or water, except such as may be necessary to maintain and operate with facilities now installed such improvements as have already been completed.” Nominally, the resolution seems to simply restrict further construction, but almost all of the construction was already completed.

In the initial CNAHR hearing on the Joint Resolution, Rep. Stephens appeared outraged that Dahlgren received $980,000 in 1918 in deficiency appropriations without CNAHR approval. He was even more annoyed that some of the money had been spent on the officers’ and commander’s quarters. He argued for closing Dahlgren altogether and framed it as meting out punishment the Navy deserved for spending so much money on the new proving ground. Committee members considered closing Dahlgren and compelling the Army to share the Aberdeen Proving Ground. Secretary Denby and the new BUORD Chief, ADM Charles B. McVay, again defended Dahlgren’s existence, demonstrating it was in fact the less expensive option. In the end, Stephens was forced to admit that because the money had been expended already, the resolution “will not do any good.” Early in December, the CNAHR chairman sent a letter to ADM Denby stating the CNAHR “desires to refrain from reporting this resolution to the House of Representatives; the committee, however will feel constrained to take this step if expenditures are not at once stopped.” Denby ordered McVay to immediately stop construction at Dahlgren.

|

|

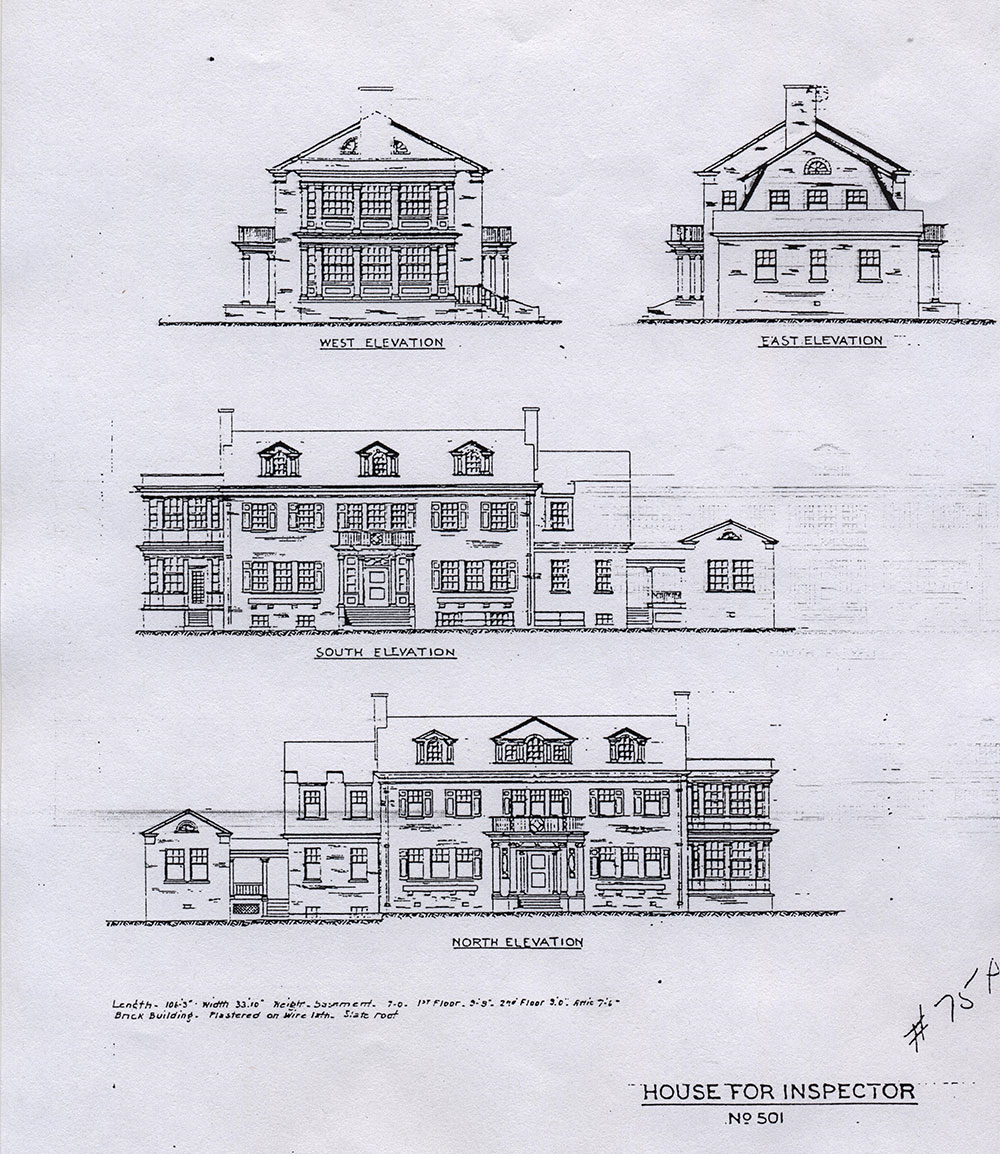

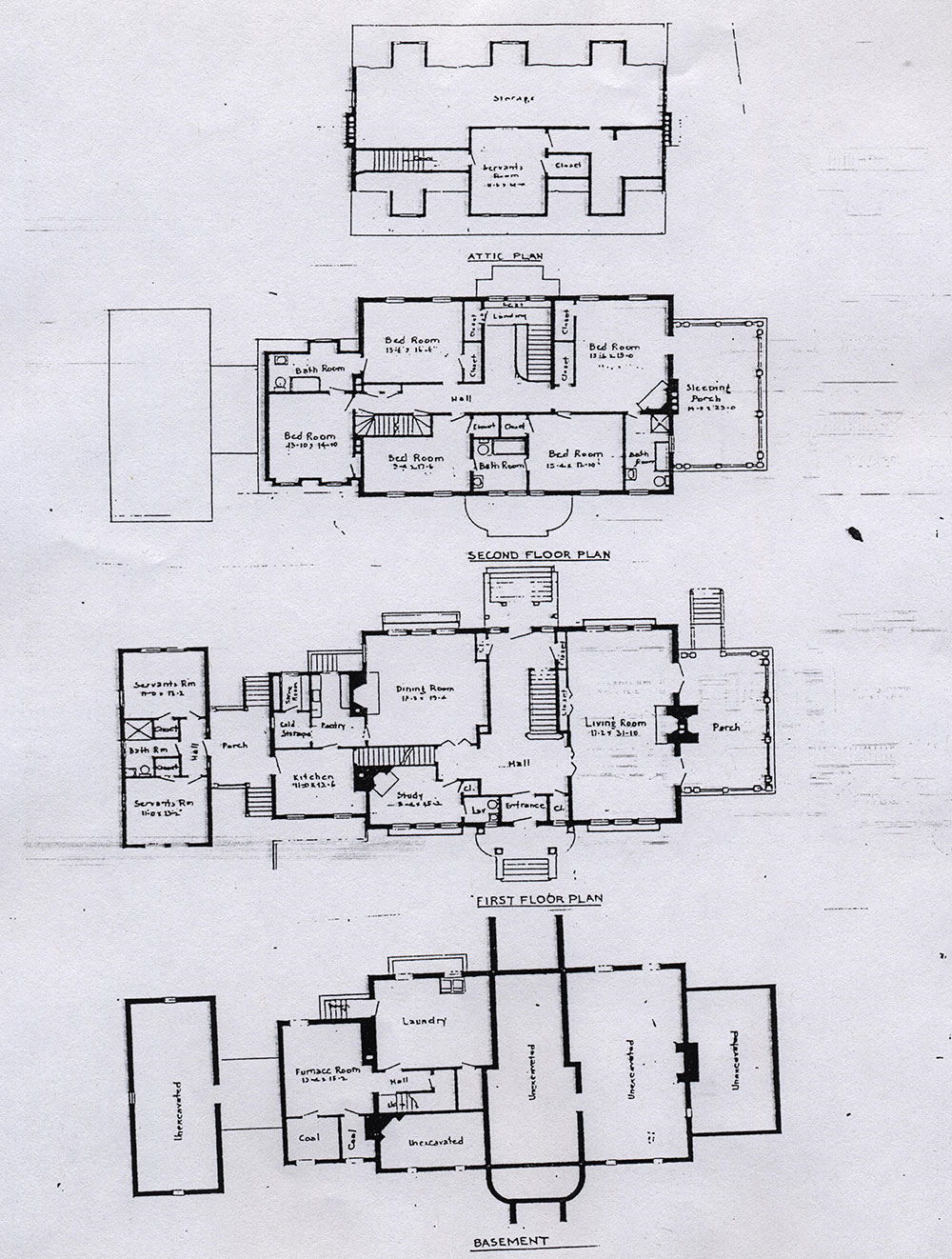

Photograph and

architectural drawings of

the Commander's Quarters

and its dependencies. |

For a few months, that looked to be the end of the fight. Stephens was likely frustrated and desperate for justification to renew his attempt to close Dahlgren. In the winter of 1921–1922, Congress signed the Five-Power Naval Limitation Treaty, an agreement between the United States, Great Britain, Japan, France, and Italy that suspended capital shipbuilding programs for 10 years, and required the U.S. Navy to scrap 26 warships. At that point, CNAHR members took a small Navy yacht—a practical means of transportation compared to driving on dirt roads—from Washington, D.C., to Dahlgren in the coldest weeks of winter and “were astonished upon [their] arrival to learn that the channel in which [they] anchored was 3 miles distant from the shore.” Once they drove the final three miles, they stepped out of their vehicles onto wooden plank sidewalks surrounded by icy mud, and looked up to see the freshly completed commandant’s quarters. On 27 February, the CNAHR called Lackey to testify at a new hearing.

Stephens opened the hearing, saying, “The committee has visited Dahlgren and the attention of the committee was called to the building of a commandant’s home… and officers’ homes at what was considered an excessive expenditure.” He proceeded to question Lackey in an attempt to discover who had authorized the construction of such grand commandant’s quarters, for which Lackey partially assumed responsibility because he had drawn up the plans for the buildings. Because of the cramped quarter at Indian Head, Lackey wanted to build something more spacious and accommodating at Dahlgren “where a fair-sized committee or commission could be entertained in proper manner by the Government or its representative when called upon.” However, some committee members left the hearing still under the opinion the cost was inappropriate.

On 18 April 1922, Stephens proposed an amendment to Naval Appropriations Bill, H.R. 11228 that read “no part of this appropriation or any other appropriation contained in this act shall be available for expenditures at the naval proving ground, Dahlgren, Va. except so much as may be necessary to maintain the station on a closed-down basis.” Before the House of Representatives, Stephens and Mudd argued Dahlgren should be shut down due to all the flaws that they had teased out during prior hearings. They capped their argument off by compelling the House to see it as a patriotic duty to close Dahlgren, because it was an unnecessary war expenditure. They argued that guns could be proved at Indian Head and ranged at Aberdeen Proving Ground or on ships: “there is no reason why these guns can not be ranged as they have been ranged heretofore, from the battleships.” The amendment met with some opposition from Democratic Congressmen, but eventually passed in the House.

The Naval Appropriations bill moved on to the Senate and to the Subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations. Even more than the House, the Senate had been embroiled in the debate over the Treaty of Versailles two years prior. A minority of Senators, deemed the Irreconcilables, had blocked the Treaty’s passage. Two of them appeared before the subcommittee in the hearings: Senators Miles Poindexter (R-Washington), an isolationist, and Joseph France (R-Maryland). France was one a few Senators who were “philosophical optimists who believed strongly in the effectiveness of nonmilitary force as a means to almost unlimited ends.” He did not express this sentiment outright in the proceedings, but nonetheless, the bias must be taken into consideration.

.jpg?ver=2018-01-22-165546-593) |

| Senator France |

|

| Senator Poindexter |

|

| Senator Carter Glass |

The subcommittee held hearings on the amendment in May and June of 1922 that ushered in a change of a tone from the procedures in the House of Representatives. They called ADM McVay, who stated, “Indianhead is of no value as a proving ground whatsoever,” and Dahlgren was a necessity. Most of the members tended to believe him. When Congressman Stephens and Sen. France appeared before the subcommittee, senators challenged Stephens with great skepticism. Stephens arrived with a change in tactics. He and France attempted to argue their decision to eliminate Dahlgren in favor of Indian Head was purely “from an economical standpoint, from the standpoint of not wasting money and not duplicating the work of the Navy.” Fortunately for Dahlgren, Sen. Carter Glass of Virginia out-debated France and Stephens in the hearings. Toward the end of Stephens’ statement, Glass sent a particularly revealing retort at them, asking “Then why not have them abandon Indianhead—because it is in Maryland?” The comment apparently caught France and Stephens off guard, because France sputtered, “No, but because there are two plants in Maryland. I might add that we were not very anxious to have them there, also. There are two plants in Maryland, one at Indianhead and one at Aberdeen, and an additional plant at Edgewood. Upon those three plants all of this testing can be done,” seeming to both contradict himself and actually confirm Glass’ point. Stephens proceeded to read a tangentially related statement from a previous hearing.

Sen. France and Congressman Stephens proved to be no great champions of the amendment in committee. When the bill was presented before the Senate on 16 June 1922, it carried a recommendation from the committee to remove the amendment that would close Dahlgren. Sen. France took the floor once more to defend the amendment. France hinted to an as-yet-unmentioned potential proving ground in New Jersey, saying, “I believe it is possible even now for the Government to secure the use of that 14-mile range without any substantial charge,” and implied the Navy could have it as a substitute for Dahlgren. However, he cited no reports or concrete evidence.

Sen. Miles Poindexter (R-Washington) opened the rebuttal with an almost patronizing comment: “I think the Senator from Maryland deserves commendation for the excellent manner in which he has presented this matter in which his State is interested.” Poindexter and Glass then proceeded to tear France’s argument apart, defending the Navy’s decision to construct Dahlgren and accusing France of not considering the Navy’s recommendations. When France insisted he was only proposing to eliminate Dahlgren for budgetary reasons, Glass countered, “Does the Senator suggest that the subcommittee of the general Committee on Appropriations had no regard for the question of economy in considering this question?” In just a matter of minutes, this last attempt to close Dahlgren was over. The Senate voted to strike the amendment from the bill.